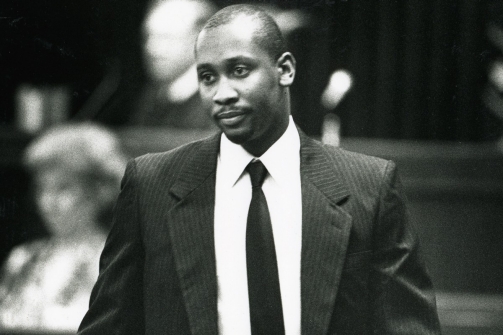

On September 21, 2011, at 10:53 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, Troy Davis was executed by the state of Georgia. He was tried and convicted for the assault of two men and the murder of a third, a police officer, in Savannah, Georgia in August of 1989.

As with other capital cases in which someone is sentenced to death, there was a great outcry by individuals, groups—even the Pope—to stay the execution on the grounds that the death penalty is a form of “cruel and unusual punishment,” and should not be meted out by any civilized country. But people were not rushing to Troy Davis’ defense simply because they found capital punishment repugnant and inhumane. They did so because there seemed to be too many flaws in the trial and conviction of a man who, for the past 20 years, proclaimed his innocence.

In the time since that tragic August of 1989, no physical evidence was ever provided linking Troy to the murder of which he was accused. Seven witnesses out of nine, who, at one trial, testified to Mr. Davis committing the crime, recanted or changed their testimony. Many said later that the police coerced their testimony at the time. In fact, some evidence came to light that the initial person who pointed out Davis as the shooter, Sylvester “Red” Coles, might have been the killer himself. Furthermore, Davis was a black man convicted of killing a white police officer. The pressure by the state to get a conviction in this case was unrelenting, and it seems that Mr. Davis was convicted by the state as a small attempt to achieve justice.

Troy Davis’ attempts to appeal his case were greatly hampered, especially in 1995, when the federal funding of the Georgia Resource Center, which helped represent Davis, was cut by 70%. There was too much work needed to prepare for his appeals, and simply not enough resources.

Former federal prosecutor and contributing writer to CNN.com, Mark Osler, shared with his readers that the most meaningful cases in law almost always involve “a clash of virtues.”

What virtues were clashing in the case of Troy Davis?

Clearly, there was the virtue of mercy—the voices of protest in society rang out loud in attempts to overturn or at least delay Davis’ execution in the pursuit of greater deliberation. We know as a society we value mercy: otherwise presidents and governors would not have the power of the pardon. Historically, our leaders and courts have heeded the call for mercy, taking into consideration many factors tempering their judgments.

In conflict with the virtue of mercy was another societal value: The “Finality of Judgment,” a judicial power that has been in use since 1792. As Osler explains, the “Finality of Judgment,” is a concept that, “…once a verdict and judgment are rendered, it should be difficult to upset. Victims’ family members sometimes see a promise in that judgment, and finality renders a certainty to the process that some see as promoting deterrence of crime.” This is why even though Davis’ case came before the Supreme Court of the United States, the ruling against him stood. “Finality of Judgment” was derived from case law, and Osler points out that this virtue is not rooted in the Constitution of the United States, unlike deliberation and mercy.

Nor is this idea of “Finality of Judgment” rooted in our Jewish value system.

Looking at capital punishment in isolation, Judaism only allows for the death sentence in the hypothetical. The Torah lists a hosts of crimes for which the punishment is death, but in 30 C.E., the Sanhedrin (effectively the supreme court of Ancient Israel), effectively abolished capital punishment, saying that it is only fitting for God alone to use, not we flawed human beings.

But moreover, this American notion of “Finality of Judgment” implies that our judicial system is infallible, and those who implement it—our judges, our jurors, our witnesses, our prosecutors—are infallible as well. It also implies that however we behave as human beings, when we are evaluated, there is nothing we can do to change that judgment.

This is what is most troubling about the Davis case, especially around the Days of Awe and Repentance.

Throughout our High Holy Days, we read over and over about how we are being judged by the Divine Court for all our sins. We are trembling and afraid. In the “Unetane Tokef” prayer we read:

…[God], in truth You are

Judge and Arbiter, Counsel and Witness.

You write and You seal, You record and recount…

…As the shepherd seeks out the flock,

and makes the sheep pass under the staff,

so do You muster and number and consider

every soul,

setting the bounds of every creature’s life,

and decreeing its destiny.

On Rosh Hashanah it is written,

on Yom Kippur it is sealed:

How many shall pass on, how many shall come to be;

who shall live and who shall die…

And yet, we take comfort when we read:

But REPENTANCE, PRAYER and CHARITY

temper judgment’s sever decree.

We call Rosh Hashanah, “Yom HaZikaron: the Day of Remembrance.” It is a day when we come before the Divine and ask God to remember us on this judgment day. And throughout this time period, we take heart that if we are repentant, contrite, and atone for our sins, we will be judged fairly and with mercy.

We plead aloud: “Avinu Malkeinu.” We say “Avinu” first, appealing to our Divine parent, who has an open ear and an understanding heart; we then come before “Malkeinu,” our Divine Ruler. Mercy and Justice are both balanced on high. We know we have had our rough moments through this past year. We understand that we are weak and not without fault. And yet we ask for justice which takes into consideration where are hearts and minds are now. Perhaps after inflicting hurt on another, whether purposefully or by accident, we can only now empathize with the one we have wronged, and make atonement. Mercy allows for us sinners to actually grow and become better people through contrition, repentance, and humility.

What does it say about us as a nation that through the example of Troy Davis our society and judicial process has raised this value of “Finality of Judgment” over mercy and deliberation? Was Mr. Davis truly given a fair trial, given due process, and thus his demise was fated regardless? That is difficult to say since the one and only punishment our court system cannot revoke is the death penalty. We can say, “We’re sorry–we made a mistake,” but we cannot bring a man back from death once a lethal injection has been administered.

If we adhere to the virtue of the “Finality of Judgment,” then what hope do any of us have on Yom Kippur, as we stand before the open ark, pleading for a better and brighter future for us and our families?

No—Jews must reject out of hand this idea that any judgment is absolutely final. Our human condition requires us to wrestle with our decisions and actions throughout our lifetimes, to beg for mercy when we have wronged others, but then to learn from our errors and arise as more whole people.

I cannot tell you with absolute certainty that Mr. Davis was an innocent man. But nor can I tell you with absolute certainty that Mr. Davis was a guilty man. My Judaism tells me that regardless of his guilt or innocence, what made him human—and what makes us human—is both a penchant to err, and an ability to repent and forgive. How one can truly repent for a capital crime is most difficult to answer, but one cannot take back a judgment as final as death.

We are in the season of introspection and reflection, of seeking forgiveness and granting pardon. And just as we would hope and expect “judgment’s severe decree” to be tempered by our prayers and deeds on this holiday, we would also hope and expect that we can turn to one another and grant that same pardon, seek that same forgiveness. Human beings have a great capacity for mercy when we want to employ it. This does not mean we abandon vigilance in our pursuit for justice in our society, righteousness within our community, or consonance between our family or friends. What it does mean is that, especially in this season and on this Shabbat Shuva, this Sabbath of turning towards the Divine and one another, that we act in the manner in which we were created: Divinely. As the Torah states, God is:

“…merciful and gracious, endlessly patient, loving, and true, showing mercy to thousands, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin, and granting pardon.”

Our nation will continue to debate the merits and flaws of allowing capital punishment. I am saddened that in the case of Troy Davis, it seems that neither was mercy granted, nor justice served. If his life and now death has any meaning for us, it should be to humble us and remind us that humans, from the powerful to the powerless, should not rush to judgment.

Repentance takes two people: The one seeking forgiveness and the one granting it. Many of us hold grudges, have prejudices, and make snap judgments. This season is not only about apologizing and making restitution, thereby conceding we are flawed, but also being able to let go of past hurt and granting pardon. To not allow another to be forgiven is to deny them the potential of becoming better. We should not create our own internal “Finality of Judgment” in our viewing of others. If Divine Judgment can be swayed by our actions, all the more so should human judgment be.

On this Shabbat Shuva, let us become more humble, more contrite. Let our hearts be open to the repentance of others and allow us to forgive more easily. Let us find in ourselves the ability to let go of pain and stubbornness, and embrace warmth and consideration. In this way, we may help one another towards a more whole and sweet new year.

Amen.