From the time we are born, human beings have the inclination to sing. Even before we utter words or full sentences, we seem to be predisposed toward making simple melodies, giving voice to our young hearts. They may not yet be sonorous or tuneful, but these songs certainly bring warmth and joy to parents and grandparents. It seems elemental and natural. And as we grow, our singing becomes more complex: We set nursery rhymes to song; we take random words and add our own melodic strains; teachers and parents expose us to music which we emulate, make our own, or turn into something new.

What is it about singing that is so vital to the human condition? Retired Professor of Vocal Performance at Emporia State University, John Lennon (who is living, an American, and not a former Beatle) teaches:

Except for birth defects, we all begin with the ability to audibly express emotion. Most animals use sound to express emotion. The primal utterance of a newborn child is emotional resonance in response to the drastic change in immediate environment. The spontaneous release expresses the mood experienced by the neonate at that particular moment: a perfect blend of sound and movement as all energy combines in emotional release. This energy release may be observed throughout early maturation as the infant becomes more aware of the surrounding environment and emotionally responds to stimulation. Neonatal and postnatal experience is almost always an oral investigation coupled with vocal sound in response to mouth contact.

Singing expresses that which words and thoughts alone cannot. We sing in joy and in sorrow. Singing moves us in ways inexplicable. When we hear others sing, we can glean their innermost emotions. When we sing ourselves, we experience release and sometimes, relief. Singing the Blues is not about being sad, but about shedding a dour mood by giving it voice.

But that voice need not be trained in order to be expressive. Professor Lennon goes on to say:

Thinking that singing is only a ‘talent’ or an ‘art form’ is a denial of a very basic human need, the need to express emotions in a way that completely satisfies the unified BodyMind of each individual. The idea that ‘talent for singing’ is the prerequisite fosters the idea that sustained vocal sound must first and foremost be perceived as ‘pretty.’

Spontaneous sound almost always incorporates a dimension of noise in its release. In order to communicate effectively, resonance must first release the emotional expression without impediment. Emotional release effectiveness is how well it satisfies the one expressing.

Sadly, modernity has passed judgement on many of us, rendering our singing voices mute. Avant-garde composer and musican, W.A. Mathieu, describes in his work, “The Listening Book” the following:

If, in your early student life, you were slightly slower to perceive pitch relationship, it wasn’t long before you were given, by your peers or an insensitive teacher, the identity of “The One Who Can’t Sing.”

D’ya call that singing?

Stop that noise.

You be a hummer.

Why don’t you sit here, where the others can’t hear you?

Shut up.

Yuk on you.

Just move your lips.

He continues:

This is deep pain. Singing is a special code that identifies us as human—our collective password. Not being able to utter the password is a kind of nightmare a child must live out during the daytime. Pretty soon we have a kid who can’t sing and who feels partially ostracized. Then we have a grown-up, capable if not extraordinary in every way, who can’t sing.

Amusia, a musical disorder which affects processing pitch and musical memory, is actually very rare in human beings. Tone deafness seems to be more of a conditioning rather than an actual condition. In other words, those who were initially told that they couldn’t sing probably can but think they cannot.

The crime here is that there are so many who believe themselves incapable of singing. It is a denial of their innate ability to express themselves in a way wholly musical, something that is not only so vital to our humanity, but is part and parcel of Jewish catharsis.

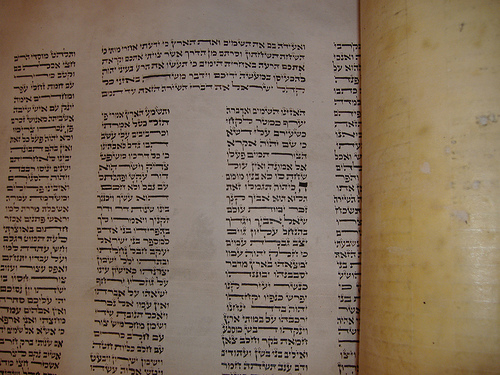

According to the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael, there are ten songs in the Hebrew Bible:

- The one that the Israelites recited at the first Passover in Egypt (Isaiah 30:29—“You shall have a song as in the night when a feast is hallowed.”)

- The Song of the Sea in Exodus 15

- The song that the Israelites sang at the well in the wilderness (Numbers 21:17— “Then sang Israel this song: ‘Spring up, O well’”)

- The song that Moses sang before he died, which is in this week’s Torah portion of Ha’azinu (Deuteronomy 31:30— “Moses spoke in the ears of all the assembly of Israel the words of this song”)

- The song that Joshua sang (Joshual 10:12—“Then spoke Joshua to the Eternal in the day when the Eternal delivered up the Amorites”)

- The song that Deborah and Barak sang (Judges 5:1—“Then sang Deborah and Barak the son of Abinoam”)

- The song that David sang (II Samuel 22:1—“David spoke to the Eternal the words of this song in the day that the Eternal delivered him out of the hand of all his enemies, and out of the hand of Saul”)

- The song that Solomon sang (Psalm 30:1— “a song at the Dedication of the House of David”)

- The song that Jehoshaphat sang (2 Chronicles 20:21— “when he had taken counsel with the people, he appointed them that should sing to the Eternal, and praise in the beauty of holiness, as they went out before the army, and say, ‘Give thanks to the Eternal, for God’s mercy endures for ever’”)

- And finally, the song that will be sung in the time to come (Isaiah 42:10— “Sing to the Eternal a new song, and God’s praise from the end of the earth,” and Psalm 149:1— “Sing to the Eternal a new song, and God’s praise in the assembly of the saints.”)

It should be noted that although the Bible speaks of singing, voices are not described—merely the words of the songs are recorded. They are words of great emotion, often of gratitude and praise. In this week’s Torah reading, as example, Moses is on the top of Mount Nebo, looking out on the Promised Land. Moses knows he will be unable to enter the land despite all his leadership and dedication in leading the Children of Israel. After wandering 40 years in the desert, his goal almost reached, he is moved to sing.

Moses implores heaven and earth to give ear to his song. He proclaims God’s faithful and true nature. He describes God as the ultimate guide and protector of the people. The song is 43 verses long, and we can only imagine the great elation Moses felt at seeing the land of Israel and the sorrow he must have felt at not being able to lead the people further.

There are no recordings of Moses’ swan song, nor are there any of Deborah, or David, or Solomon. But we know they sang. No one stood up in the midst of their emotional melody and said, like a Biblical Simon Cowell, “That was terrible, I mean just awful!” It’s even ludicrous to imagine this having happened.

And yet this happens every day. Not only when we sing, but when we express ourselves in writing, in art, or in speech. Somehow it is socially acceptable to be critical of others in how they express themselves. We listen less to what is in people’s hearts and more to how they are being conveyed. In today’s climate, a poet like Bob Dylan would never have become a critical success. Thankfully, he is considered a voice of a generation. He did it in song. And his voice resonated with so many. But what of the next Bob Dylan? Will his or her voice and spirit be crushed by a parent or teacher?

Our ability to express ourselves freely is important for two reasons: One, because in our vulnerability, when we emote, we become lucid communicators, letting others know our authentic selves; Two because when we experience others’ vulnerability and expressiveness, we become emboldened and empowered to express ourselves.

On this Shabbat, as we hear Moses’ final song, we should be grateful for a Biblical role model who was willing to let it all hang out. Moses, knowing full well he was going to die without seeing his dream fully realized, had nothing to lose in singing with passion and zeal. At the same time, none of us have anything to lose by acting likewise. There is nothing shameful in being true and authentic and expressive. It makes us more honest. It makes us more open. It makes us more real.

But sometimes we have trouble finding our inner voice. Our psychology and baggage have muted us. This is why we come together as a community. It is a place to sing together. And when we sing together, we can lean on each others’ hearts and spirits. It is comforting to sing with a friend or a loved one. As we become stronger in spirit, we then find our own voice and take that chance of being heard above the din of apathy and despair. Each of us has something to sing about—some have tragedy and loss which needs to be heard; some have joys they must share.

When we finally find our voices, may we, as the Psalmist suggests, sing to the Divine Source which strengthens and supports us. The song is within each of us. Now let us sing!

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2012 Erik Contzius

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2012 Erik Contzius

I love what you have to say here about the cathartic purpose of singing and how that is practiced in the Bible.

Inspiring! Thank you for sharing!

This has touched me very deeply, even as an Atheist. There is so much truth here that it’s as heart breaking as it is inspiring. Thank you for these words.